BOOK REVIEW:

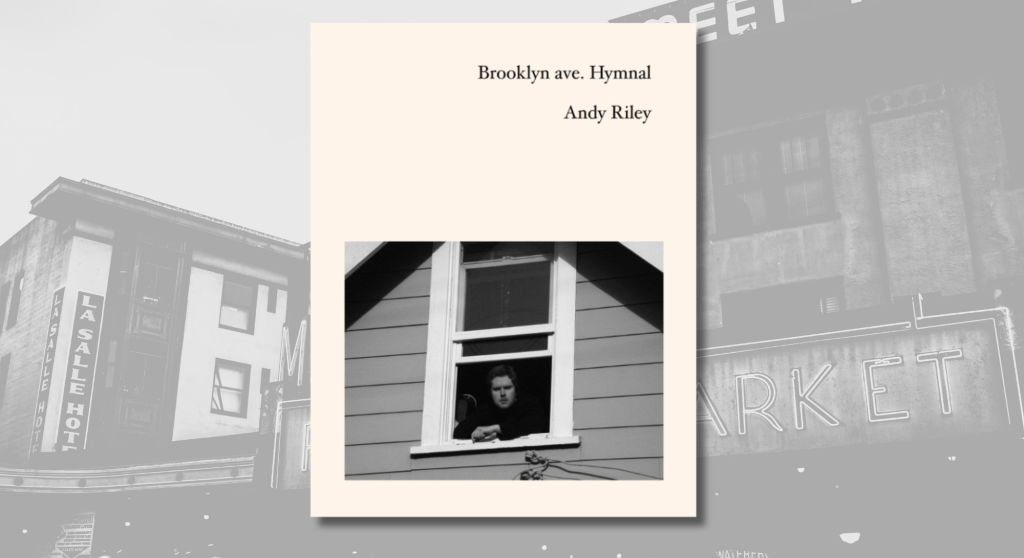

BROOKLYN AVE. HYMNAL BY ANDY RILEY

A BOOK REVIEW BY EDEN HEFFRON-HANSON

One of my main impressions of Andy has always been that he prints chapbooks like other poets print rejection slips. The first time I met him, at Wolverine Publick House in Fort Collins, he was carrying a bundle of self-printed books for the reading. Later, when he invited me over for homemade absinthe, he had more from the past year for me, from the “early years”. While I have long delighted in his exciting cacophonic phrasing and interesting imagery, what I have most admired from him was the nonstop DIY ethic which kept him writing and printing instead of waiting for approval.

Thus, it is with great pleasure I am reviewing Andy Riley’s debut 87-page serial poem Brooklyn ave. Hymnal. A book about moving to Seattle that is so rife with character observations and daily ennui, chronic pain and stunted sex drives, that truly it will leave you searching for an answer to the question, why would you move to Seattle?

Maybe it’s so Riley could “get out to see Red Pine” from Seattle or live on the street of the “high school where sir mix a lot went”, perhaps it’s so he could live a ten-minute walk from “three old growth trees”. Or maybe Riley moved to Seattle for the same reason anyone moves anywhere, to see something new and make sense of it, to turn around and produce a work of art grounded deeply in a place and time that hadn’t grown dull from repetition. What we receive is a poem facing down the alienation and loneliness of being literally ungrounded. We receive addresses to the dead and separated, to long distance friends, and the ever-aloof state of Colorado.

We are introduced to a poet navigating public space and the struggle for connection between strangers. I delighted in the man in camo pants trying to train surf, the howler under the tunnel on the light rail, and the couple who waves back at the narrator from under the bridge. The poem builds us a world of characters vying for attention, a series of exhibitionists mirroring the short, showy writing of the poetry itself.

Having read shorter renditions of Riley’s writing, the sometimes-eclectic chapbooks he described as his “EPs”, I was excited to see how his style would take to a book-length poem. The use of short sequences allows for concentrated bursts of energy sympathetic to his style, while the relationality allows for an opening up into moments of satori. One of my favorite sections in the poem is election day which both contains the rapid fire “bodily steam footfalls mirage/ like climbing a ladder” and the wide-open couplet “hate of the unknown is traditional/what of this hate of the known”. The book also shares my love of nouns you can grind your teeth on. Brooklyn ave. uses to full effect the regional “noggins”, the scientific yet punk “oxytocin boot black”, and a whole quatrain about “priapism”. More space allows Riley more exploration in word choice and sound, and it’s lovely to see him opt for a yummy and timely dialect.

The building blocks of short poems translate into a feeling of discovery throughout each that Riley deftly sustains through the book.

Riley’s adjective phrasing, which delights in novel syntax while also bending the grammar of sentences, help him create metaphors from bite sized lines of language. Lines like “no flower columbine”, “smack gridlock/migraine-iacal car-ships” or even the simple “ATM smoke shop” recreate adjectives from modifiers into carriers of essential natures for each of the nouns. The building blocks of short poems translate into a feeling of discovery throughout each that Riley deftly sustains through the book.

The only places of the book that confused me were moments of rhyme where the poet slips into a register more reminiscent of Shelly and Dickinson than Weiners or Spicer. Compared to the breakneck speed at which the poetry generally moves the section “the dawn nay dies/it flies.” or “ah/T-shaped wisteria” felt lethargic. However, the register never seems to be employed without irony or self-awareness and there are plenty of moments where rhyme or abstraction is seasoned to taste in the poem. There are also brilliant sections subverting form such as the telegram-like “when I speak” section. Overall, the spots that stick out and interrupt the flow of the poem are done with subtlety and creativity that brings the larger project in balance with itself.

We may never know why one moves to Seattle. However, we do know what one does with the experience. Riley gives us an istoria making sense of public space and loneliness in a large explorative sequence. Brooklyn ave. Hymnal is an assertive ennui filled poem making sense of the daily mess that we each navigate to produce art. The creativity and power of his style is on full force here while his craft remains a love letter to poets like John Weiners and Frank O’Hara that have long informed his work. It’s a delight to have such a strong showing from such a young western poet.

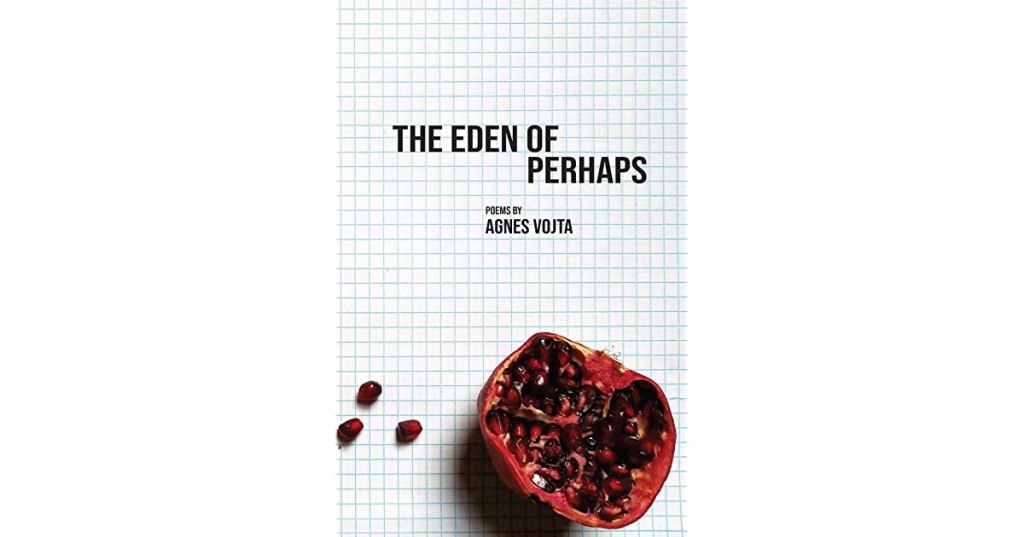

BROOKLYN AVE. HYMNAL

BY ANDY RILEY

AVAILABLE THROUGH PILOT PRESS

Eden Heffron-Hanson is a writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She traditionally writes love poems but in her down time would looooove to review your work (edenheffha@gmail.com or @edenheffha on Instagram). She has been published in Beyond the Veil Press, South Broadway Press, and Mountain Bluebird Magazine.